Saints care about art (and about us) more than we think.

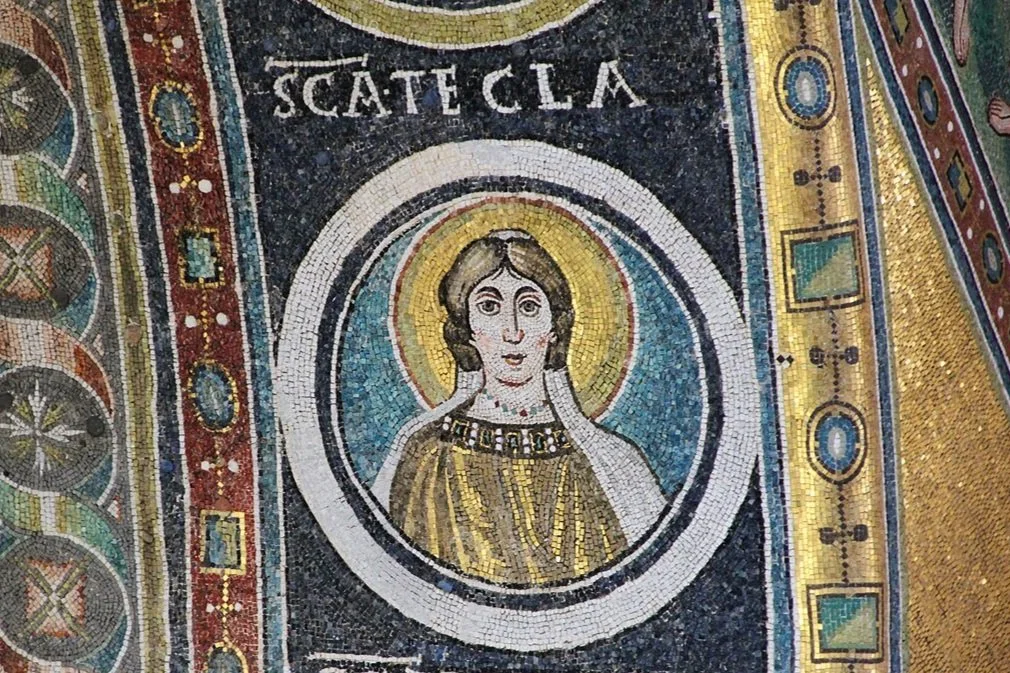

St Thecla, pictured with the world’s smallest lion. No miracle needed to escape martyrdom in this artwork.

I suspect the saints must have a particular affinity with art. After all, that’s how most us come to know them: a holy card at a piety stall, a stained-glass window, an Instagram post.

For sure, their words affect us too. Who hasn’t been struck by the wisdom of one of our brothers or sisters in Heaven, who seemed to have been able to read the landscape better than those around them, and knew the struggles we would face centuries before we came into existence?

If our knowledge of a saint was only in an image, it would be a poor friendship we’d have with them.

But it would be a similarly poor friendship if we lacked any image at all. A case in point is a recent saint from the Philippines – St Pedro Calungsod. Only the second Philippino saint to be canonised, St Pedro was a catechist serving in a foreign mission when he was martyred by an axe-wielding aggressor.

Pedro was 17 years old, didn’t seem to be anyone important in his community, was of no particular wealth or status, and so had no image. And yet sometime before his canonisation, an image was created. It showed St Pedro as a young Cebuano teenager, looking into Heaven and holding a palm branch. He now had a face, and we could gaze with our eyes into his eyes.

St Pedro Calungsod, by artist Rafael del Casal.

I was in the Philippines serving as a missionary for several months in the lead up to St Pedro’s canonisation. I was in Cebu – the same island St Pedro had come from – and I was struck by how well the artist had imagined Pedro. He could have been the brother of any number of the young Cebuano men I encountered.

And that is the point: he was one of them. Give a saint a face and suddenly they are our sister, our uncle, our cousin, our neighbour.

A wonderfully titled book by Colleen Carroll Campbell is My Sisters, the Saints. I confess I’ve never read the book, but the title often edges its way into my thoughts. The saints are my sisters, my brothers.

“Give a saint a face and suddenly they are our sister, our uncle, our cousin, our neighbour.”

A wonderful story I once heard a religious sister tell, was how she ended up in the most unlikely circumstances to find herself enrolled in a summer course exclusively on St Thomas More, the English lawyer and martyr.

Although at every instance she had made a choice which led her away from that line of study, she found herself facing a summer with a saint she wasn’t particularly close to.

But when desperately ploughing through the readings for the first class, she was struck by a writer’s observation: St Thomas lived the virtue of friendship perfectly.

She read on, but the thought kept coming back: he lived the virtue of friendship perfectly. Finally, unable to continue reading, she paused to pray. What did this mean? And then it dawned upon her: he lived virtue of friendship perfectly - and he wanted to be her friend! That revelation transformed her attitude to her study, and led her to undertake a thesis on St Thomas More.

Like all things that are truly of God, the sister’s experience was a blessing to those around her. For me, it has remained as a truth in my mind: the saints want to be our friends.

The saints want to be our friends

Saints are not merely holy men and women who have run the race to Heaven, and whose example we should emulate. And they aren’t simply saintly slot machines either, to pray to when we’ve lost something or need a daily miracle. They are meant to be our friends, our perfect friends who can be closer to us than any of our earthly friends can be because – and this is the deeply awesome part – they no longer have anything to do with sin.

Sin is what separates us from one another. In Heaven, we will live in perfect union and communion with one another, even after we have our bodies back. The saints are living this right now. And they are reaching out to you and to me with the hand of perfect, sin-free friendship.

So what has any of this got to do with art?

St Thomas More, who is said to have lived friendship perfectly.

I used to write for a newspaper, and for several months wrote a column dedicated to telling the life of a saint. While I thoroughly enjoyed learning the facts of a saint’s life, and hopefully communicated it engagingly to the readers, it was nothing to the experience of insights, sense of nearness and joy of being in a saint’s company that I have experienced as an artist.

It may be because I have a charism for art, but not writing, or because when we draw close to God all words fall away, except one. It can be no coincidence that in Heaven we behold the beatific vision, not the beatific paragraph. Of course I am joking – Jesus is the Word of God, and the Bible is the Father’s Word spoken over us and to us.

“The saints are reaching out to you and to me with the hand of perfect, sin-free friendship.”

It is both words and art which signify humanity.

Cave paintings are proof of human presence, just as our affinity for language is distinctly human and is what allows our humanity, culture and faith to flourish. It is deeply disturbing then that it is particularly the fields of art (including film) and writing which AI seems most destined to invade.

But I digress.

Let me tell you about my friends, the saints.

St John Vianney

St John Vianney – or St Jean Vianney – was a saint who always seemed distant to me. He was a priest, while I am a single young woman. He famously lived on moldy potatoes, while I find fasting from meat on Fridays difficult.

And he looks so severe with his shoulder-length white hair and 18th century priestly garb. Yes, he’s often depicted hands clasped and smiling, and yes, I know he was extraordinarily humble, but I only read a little of his sermons and it was enough to mark him in my mind as severe.

Admirable? Yes. Holy? Definitely. Close to me? It didn’t feel like it.

But then one evening in the days I was still fitting in art around lunchtimes at work and in the scraps of my time before bed, I thought of a friend who would shortly be ordained to the priesthood, and how nice it would be to make a card for him, rather than buy one.

But what to draw that wouldn’t be tacky? And then I realized: St John Vianney! The patron saint of parish priests would be perfect.

St John Vianney, looking severe.

I found an image of the classic painting of the Cure of Ars (long in the public domain) and sat down to work with graphite.

I sketched a rough outline, began to lightly put in the details, and gradually St John Vianney began to appear.

And I found, as I’m sure all artists do, that when making an impression of another artwork, your work takes on a life of its own. In my case, St John Vianney’s eyes were dancing as they looked at me with a twinkle that I’d never noticed before. And he smiled. He had the same wrinkles and thin lips as the original, but there was warmth in his expression as he gazed at me.

“He famously lived on moldy potatoes, while I find fasting from meat on Fridays difficult.”

We never create in a vacuum. I had been dwelling, as I often did, on my vocation and how I would like to meet my future husband and how distant marriage seemed, and I was possibly even praying a long novena at the time. And it struck me – as it had never struck me before – that St John Vianney, rather than being a cold and distant intercessor, was the perfect saint to draw close to on this issue.

As a parish priest he would have performed many, many marriages, and knew the importance of a good and holy spouse.

My card featuring St John Vianney, after the classic painting of the saint.

Rather than our vocations and lives being distant, I could especially ask him for his intercession to meet my husband, as it was something in which he would have been very experienced.

And then at the turn of the year, when I had been planning to choose St Joseph as my patron saint (along with half the Catholic world, as we were then part way through the Year of St Joseph) I happened to look up and see St John Vianney’s piercing gaze staring at me from the card I’d created on the mantlepiece. I realised: I was meant to choose St John Vianney this year. So I did.

Our friendship was born through art.

St Thecla

If you haven’t heard of St Thecla, you’re in good company. Or at least you’re in company with me. I was approached by a customer on Etsy about creating an artwork of this saint for a child’s baptism, and had to confess that I had no idea who the saint was.

The internet search I did was not promising. She has been venerated since the early Church but was taken off the universal calendar in the reform of 1969 – in the same reform that removed St Christopher.

I wondered: Could I even make an artwork about her? What if she wasn’t real – would that be a sin?

St Thecla, from spurious saint to surprisingly edifying.

Our Orthodox brothers and sisters still venerate her, however, and after much digging I realised she hadn’t actually been suppressed but rather that her feast day had been removed. We were free to venerate her.

A commission is a commission. As a journalist I learnt that if someone comes to you with a story, it’s a good idea to listen because it might just be the Holy Spirit.

“I wondered: Could I even make an artwork about her? What if she wasn’t real – would that be a sin?”

So I drew St Thecla. A convert of St Paul’s, she left Iconium and travelled and spread the Gospel. She survived martyrdom by a series of miracles, and earnt the title ‘pro-martyr’ despite dying of natural causes in her old age.

One story was that she had been thrown to the lions, who became incredibly tame in her presence. I decided to depict her with a lion, as well as the cross she is often shown holding, and a scroll of the Gospels.

As I drew Thecla, a funny thing happened: my heart began to change. I remembered the many miracles that have been attributed to other saints, which makes her own miraculous story less of an outlier. And the earliest Christians weren’t chumps – they cared about who was venerated as a saint. I found myself asking her for prayers and as her image became more and more developed I realized: this is a strong woman.

I’d shared by doubts, along with a peek at the work-in-progress, with one of my housemates.

My artwork of St Thecla, pictured with a lion, a scroll of the Gospels and a cross.

Later that day when I announced I was nearly done, and that I was now almost convinced St Thecla was real, my housemate came back with a zinger: the whole day, after getting a glimpse of my artwork, she had St Thecla on her mind. She had been calling on her for prayer and couldn’t get the worship song Lion and the Lamb out of her head.

She too was now convinced of the saint’s authenticity. It seemed like St Thecla was wanting to be known.

I was struck by the fact that it was once again through art that a saint had drawn close.

But of course this is all subjective evidence: feeling close to a saint, having revelations about them, worship songs in our heads. What about external proofs that the saints care about art?

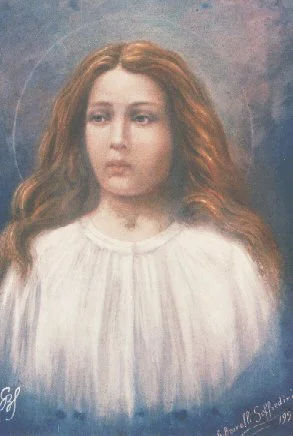

One saint who I think must care very much is St Maria Goretti.

St Maria Goretti

If you haven’t encountered this beautiful Italian saint, then you’re in for a treat. Aged just 11 years, St Maria Goretti resisted the sexual advances of 20-year-old Alessandro Serenelli who would violently stab her 14 times, leading to her death.

Lying in hospital, with Alessandro in jail, Maria was asked by a priest if she forgave her attacker. Her response: "Yes, for the love of Jesus I forgive him ... and I want him to be with me in Paradise. May God forgive him, because I already have forgiven him.”

St Maria Goretti is a favourite Confirmation choice for many young girls, and several years ago I travelled to her hometown of Nettuno with a friend who – unsurprisingly – had chosen her as a Confirmation saint. However, I’m no expert, and don’t have a strong devotion to her.

St Maria Goretti, pictured in white.

I never set out to draw her at all. I had intended to draw Our Lady, being aware that my greeting card collection had no individual card for Mary – a serious gap in a Catholic greeting card line.

I like to be inventive with Our Lady, including making up new titles for her. While sketching the beginnings of an artwork, I played with the idea of having her arms full of blossoms and calling her Our Lady of the Flowers.

And then came the thought: this is how St Maria Goretti appeared to Alessandro Serenelli, who remained unrepentant in prison for years after her death.

“Yes, for the love of Jesus I forgive him ... and I want him to be with me in Paradise. May God forgive him, because I already have forgiven him.”

The story is this: one night in a dream, he saw little Maria approach him carrying 14 white lilies – representing the 14 times he’d stabbed her. He woke completely repentant, made his Confession and on leaving prison became a Franciscan Tertiary. In an incredible act of mercy and compassion, Maria’s mother Assunta forgave Alessandro, and they sat side-by-side at her canonisation ceremony.

So instead of Our Lady, I decided to draw little Maria with her arms full of lilies. I thought a white dress would be appropriate, and a headscarf with a pattern of red flowers. But I like to feel my way through an artwork, adding some, taking some away – a process that is both involved and evolving.

“One night in a dream, he saw little Maria approach him carrying 14 white lilies – representing the 14 times he’d stabbed her. He woke completely repentant, made his Confession and on leaving prison became a Franciscan Tertiary. ”

And for some reason, in what seemed like the most innocent switch, I decided to make her dress red. Deep red, like wine. I added a purple apron, to emphasise her youth, and worked on the lilies. Finally, I decided to depict her with her eyes closed, and with a smile.

To draw a saint might seem simple, but in feeling out who they are and how they should look, the final artwork often takes several days.

Sometimes, I find that I’m in a rush to get it done and work at it constantly. At other times, I delay and procrastinate. With St Maria, I wanted to procrastinate. But something kept whispering to get it done.

Now I’ve mentioned that I know St Maria, but it shows how little my devotion is in that I can never remember her feast day (it’s July 6, if you’re curious). And so I had no idea when beginning the artwork that her feast was only days away. When I discovered that, I sped up and finished the image.

My artwork of St Maria Goretti, with a wine-red dress.

I was struck by the timing: I hadn’t intended to draw her, but she had come to my mind. I was going to finish her in a leisurely way over a week or two but discovered that I was only days away from the feast set aside to specially honour her. I felt St Maria Goretti’s hand, and that – in a curious way – she wanted to be drawn.

And if she wanted to be drawn, then surely she wanted it to be shared. So I posted the artwork on my personal Facebook page, told her story and hoped it would touch someone.

“I felt St Maria Goretti’s hand, and that – in a curious way – she wanted to be drawn. ”

A week or so later I was in the kitchen with my ipad, and realized I hadn’t shared with my St Thecla-devotee housemate about drawing St Maria Goretti. I knew she would be interested as St Maria is, of course, her patron saint.

As she looked over my artwork, her eyes lit up and she made a few nice comments.

A good start, I thought.

But then came a remark which took me completely by surprise: Oh, you’ve drawn her in her First Holy Communion dress.

Sorry, what?

She explained: St Maria Goretti – who famously had to strive to achieve her First Holy Communion despite not attending school – did not wear the usual white to her ceremony, but instead wore a wine-red dress, bought especially by her mother for the occasion.

My jaw dropped.

What were the chances of me accidentally choosing to depict St Maria Goretti in that dress? Almost zero to none. My logical brain had told me to make it white. But I had been innocently guided into changing the customary white into a deep, wine red.

So how to understand all this?

I think St Maria Goretti cares about how she is depicted in art.

I think she knew that she was being drawn, and I think she wanted to be in her red dress.

And perhaps she wanted to let me know that she is much closer to me than I imagined.

Naomi Leach is a writer and emerging artist and illustrator based in Sydney Australia.